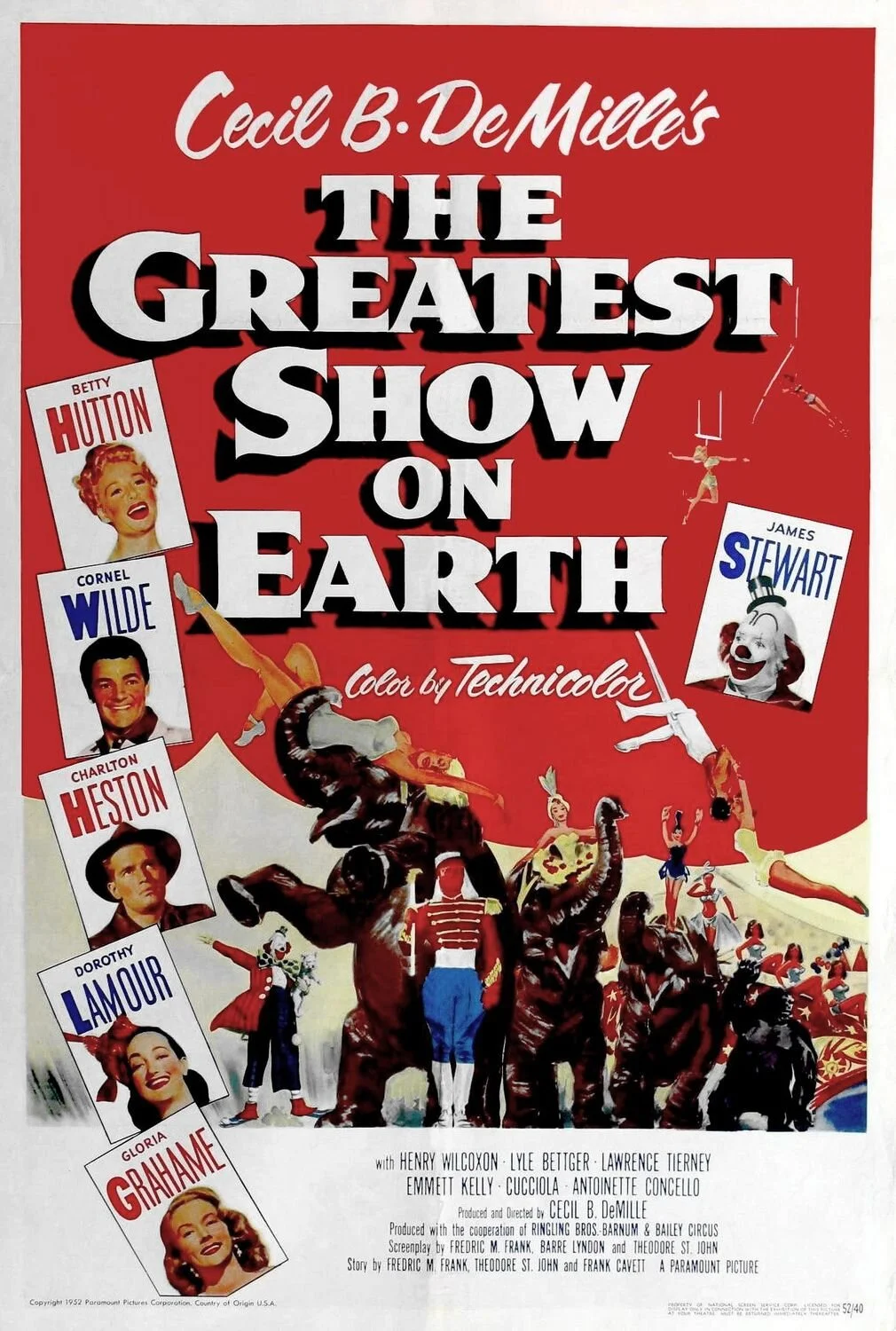

The Greatest Show on Earth (1952)

Written by Fredric M. Frank, Theodore St. John, Frank Cavett, & Barré Lyndon

Directed by Cecil B. DeMille

Although I rarely went to them, I’ve always been a fan of the circus. I’m not entirely sure why, but the idea of this traveling troupe coming together to put on a show always held some sort of appeal for me. Even now, when driving around, seeing the big top in the distance gives a certain, momentary thrill.

I was expecting The Greatest Show on Earth to be a bit of a precursor to last year’s The Greatest Showman, but other than the idea that the featured circus was Barnum’s brainchild, it isn’t. What’s featured is a strange mix, a film that is both part fictional drama and part documentary. It’s strange because, for me, it succeeds in one and fails in the other.

A fun fact: James Stewart plays a supporting role as a clown that never removes his makeup

As a documentary, the film is intriguing. As I mentioned, I’m a fan of the circus, so seeing the work that goes into putting on the show was fascinating. The film features actual performers and workers from Ringling Bros., so the line of what is real or not becomes blurred. Seeing the difficult and dangerous work was much more interesting than the fictional plot, to the point where when one of the actors appeared (especially the non-performer roles (see: Charlton Heston)), it felt like an interruption of a much more interesting scene.

The three stars of the film: Cornel Wilde, Betty Hutton, and Charlton Heston

It’s not that the fictional plot was bad, it’s just repetitive. Betty Hutton is an up-and-coming trapeze artist, and she’s in love with the circus Road Manager, played by Heston (who has the least likable character in the film). When he books an established star trapeze performer, Hutton must fight for the center ring, and she and the new artist flirt and battle, and she and Heston fight and make up and fight and make up and there’s an accident and good lord it’s all paint by numbers. Of all the leads, Hutton is the most watchable, particularly after the film’s climax, but it’s a slog of predictable drama to get to that place.

The climatic train crash

The climax features a train-on-train collision (because of plot reasons), and while the majority of the effects look pretty silly by today’s standards, it is easy to imagine that they would have astounded audiences in 1952. Also, director Cecil B. DeMille has his actors actually learn the circus acts they depict, so that is also entertaining (there’s obviously some moments of doubles, but many times, it is the actual actors performing these feats, which is always a joy to see).

Ultimately, I find myself without much to say about this film. I think its Best Picture win can be attributed mostly to its scope, not necessarily for its actual achievements. Like when I watched The Greatest Showman, watching the film now is a little bittersweet, since the featured circus has closed after more than 100 years of performances, but at least the film gives a great overview of the magic and mystery of the circus, of a heyday that has long since passed.

FINAL GRADE: C