All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

Written by Maxwell Anderson, George Abbott, & Del Andrews

Directed by Lewis Milestone

War, as a background for storytelling, is fertile ground: battlefields are littered with stories waiting to be told. It’s not so surprising to me, then, that the third Best Picture winner, All Quiet on the Western Front is the second out of the first three winners to deal with war, especially considering that the Great War had ended barely a decade before the film was released.

I will admit, upfront, that this movie struggled to hold my attention. Not that it was a bad movie; it’s actually quite good. I just, personally, have always struggled with war movies...they just aren’t my cup of tea. Added to that is the fact that at this point in filmmaking language, we see more of a push towards plot, and not towards character (and again, I don’t mean to say that there is NO characterization), that it was harder to care about some of the early casualties in the film, because as a viewer, we haven’t gotten to know them pretty well.

Main character Paul, in school, fantasizing about joining the war

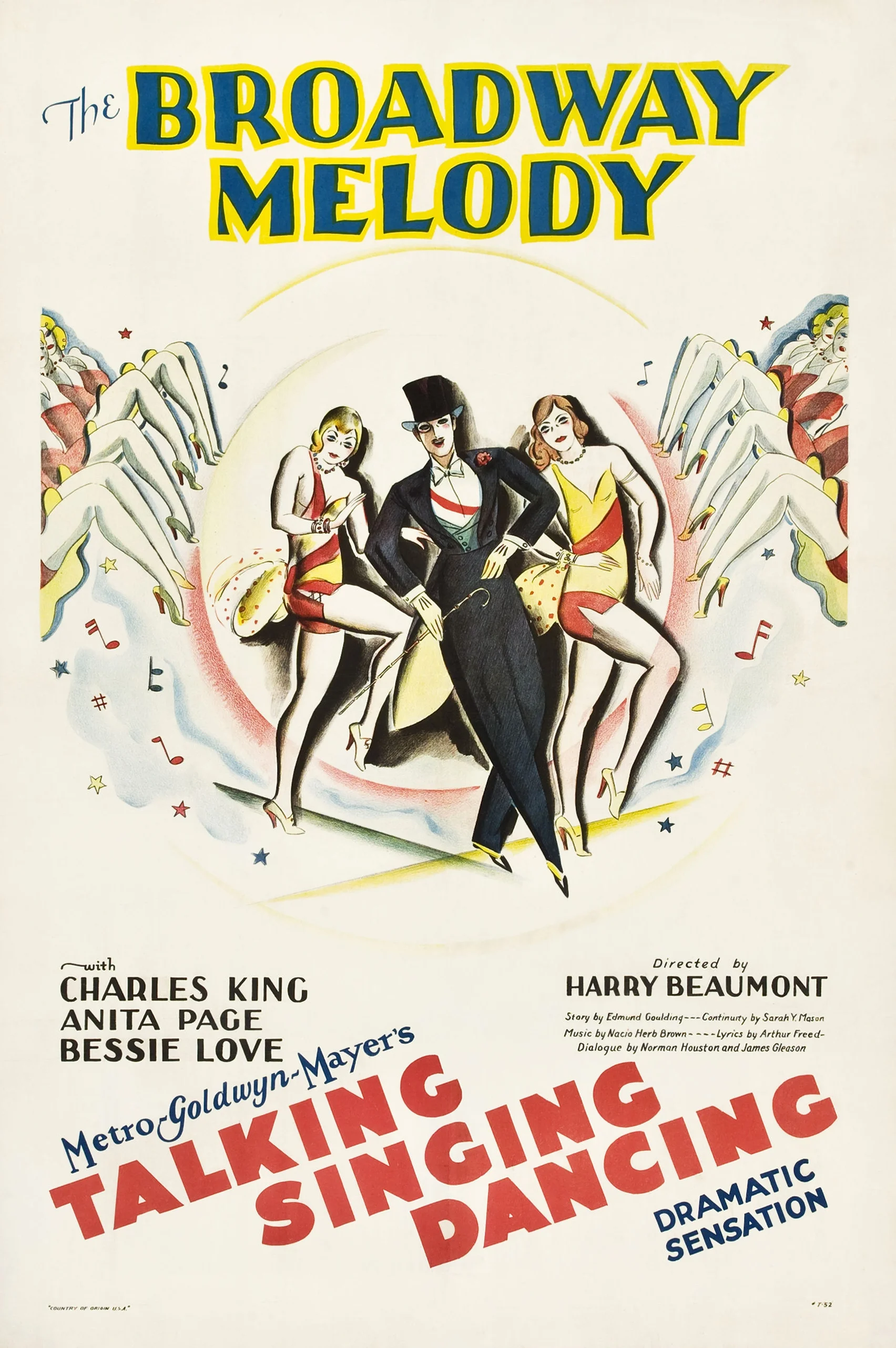

But, let’s not get ahead of ourselves here. After the blasé The Broadway Melody, Front is a breath of fresh air, tackling a surprisingly large amount of heavy thoughts through its just-over two hours of length. A big positive, in my opinion, is the welcome return of moving cameras! Nearly every shot features a camera move of some kind, and it is wonderful to see directors playing, testing to see what they can do (especially after Melody, in which everything was locked down). There’s also a great cinematic technique to show fantasies of the young, soon-to-be army recruits (I have no idea if this was the first film to use this technique (probably not), but it’s the first Best Picture winner to do so). It highlights the maturation of The Filmmaker, and it’s exciting, to me, to see the evolution of the cinematic language.

One decision that was tougher for me to accept is the lack of underscore. The film is not a silent one, but very little music accompanies the film, besides diegetic sources. The only exception that comes to mind is in the final scene, where the faintest of music can be heard. As a film music fan, this does make the viewing more difficult for me. While I agree with the concept that a film should be able to tell its story effectively without the use of score (and this film certainly does), I also agree that the score helps elevate the emotion; it helps convey the film’s message to the audience. Conversely, I would say the lack of score allows the viewer to make his or her own assumptions about the emotions and message of the film: I certainly came away from the film with a very clear idea of what the film is trying to tell me, but someone else might watch the film and come away with a very different interpretation. And, who is to say either of us would be wrong?

The aftermath of war

Since we’re on the subject of interpretation, let’s discuss mine. For me, the film tackles many different topics, but all of them essentially being anti-War. The biggest over-arcing theme is taking young, idealist men and throwing them into the horrors of war. Initially, in this film, those horrors were difficult to understand (when compared to, say, Saving Private Ryan), as it took a while to see any battlefield action. There was an interesting dividing line of what could, or could not, be shown. No one is shown actually being injured (for example, we don’t see any bullets enter a body), but the film is plenty okay with showing the aftermath (one standout shot was an allied soldier reaching for a barbed wire fence as an explosion goes off around him. When the smoke clears, just his hands are hanging on the fence: we don’t see them being ripped off, but we see the aftermath).

Paul, after experiencing the horror of war

As the film goes on, more themes become introduced, such as how war makes boys become men, or how it’s an endless cycle: young boys enlist, become hardened, some die, and get replaced with new young boys. Even the concept of PTSD, or soldiers who never really stop fighting the war, even when they’re home, is touched on (considering that this was made before WW2 or the Vietnam War, this is amazing foresight). And, even a little taste of, what Hamilton says, “Who lives, who dies, who tells your story” (I haven’t mentioned it yet, but the film is told from the point of view of the Germans, not the Americans. And, they don’t believe they’re at fault. It’s a very interesting dynamic). It’s a lot of different things, but I’d argue that, rather than trying to be too much for too many people, it actually makes the film more accessible, as people can latch more onto the themes that impact them directly.

Platonic, but seemingly unthinkable today

There is one last minor filmmaking technique I want to mention, and that is how the film handles love and sex. It’s still 1930, so even though the Hays Code was just about to be created, there’s a lot that still isn’t shown on screen. There is an implied sex scene between two characters; we, of course, don’t witness it: we see the seduction and the aftermath. That aftermath is most interesting, as the camera simply faces a wall, and we hear the two characters talking in bed. It seems so...quaint, in a way, that 78 years ago the thought of showing a man and woman in bed, doing nothing but talking, was inconceivable. Conversely, all three Best Picture Winners have, so far, shown mild male to male affection (kisses on the cheeks, etc.), and this is shown without the bat of an eye. I point these out simply as food for thought on the progress of society.

As I mentioned, I’m just not a fan of war films, but I enjoyed this film more than I thought I would. It’s a great example of a film trying to educate and entertain its audience at the same time, but sadly, the lessons it attempts to teach would be unheeded, both then, and even now.

FINAL GRADE: B